SPORTS MARKETING

Butts in the Seats, Eyes on the TV...

Changing Demographics

Is 18 to 34 still the most coveted demographic?

I turned 35 on Monday. And sure, getting older sucks. But it’s not my hair thinning that gets me, or that thing with my knee. The real existential gut punch of it all is that on Monday, I aged out of the coveted 18-to-34 demographic.

For decades, the 18-to-34 age group has been considered especially valuable to advertisers. It’s the biggest cohort, overtaking the baby boomers in 2015, and 18 to 34s are thought to have money to burn on toys and clothes and products, rather than the more staid investments of middle age.

“Eighteen to 34 has been regarded for so long as the young demographic,” said Michael Miraflor, global head of futures and innovation at the ad agency Blue 449. “So when you age out of that you’re like, ‘OK, now what am I considered?’”

Old, Michael! And, even more sadly, irrelevant. See, literally my entire adult life, from the minute I turned 18 until this week, my opinions have not only mattered — they’ve moved markets.

For advertisers, Miraflor said, “It’s about the opportunity to kinda convert those 18- to 34-year-olds into brands and products and services they’ll use for the rest of their lives.”

Miraflor explains that these big demographic “buckets” were created back in the “Mad Men” days, when age was a proxy for interests. Young people must like fizzy soda and fast cars; old people prefer iced tea and slow cars — sell them stuff accordingly. And if you want to help an old person feel young? Sell him a sports car, of course.

This gave me an idea. What if I could use my final days of relevance to sort of pull the culture towards me? Living it up, consuming all the stuff I love, I could signal to advertisers that my taste is what’s hip. Doing so, I could move the needle toward my taste one last time … before my taste stops mattering.

So that’s what I did. For example, I love ambient music; new-agey drones and tones type stuff. Last week I went to see some ambient artists perform. I bought the ticket with my credit card — that’s a data point CapitalOne will sell to advertisers.

I also posted all over social media: dozens of tweets and likes and snaps. Together, all those data points make a little data constellation, that, if it’s bright enough, tells advertisers “Hey. Look over here. This stuff must be cool — look at the coveted young person who’s consuming it!”

End result, said Lee Maicon, chief strategy officer at ad agency 360i, “You might start to see some of that music in some of the advertising you’re being targeted with.”

Maicon, who just so happens to share my same birthday, has brought me the greatest gift I could ask for.

“Age is still valuable,” Maicon said. “It’s not the whole story.”

In the era of big data, Maicon said age is just one data point. Now, things work almost the opposite of the way they did in the “Mad Men” days. If young people get into iced tea and slow cars — or, say, seltzer, vinyl records, mom jeans — advertisers will learn that from the data, and adjust the demographics accordingly.

In addition, Maicon said that “rather than see things by demographic, we’re able to see adjacent passions.”

If I really wanted to boost the signal on my music taste, he notes, I might have spent the last week consuming fashion and gadgets and fine dining, too. Then the data would correlate my taste in music with all of that other, coveted consumption.

But most importantly, Maicon assuages my biggest fear. That culture-hacking experiment I’ve been performing using my last week in the coveted 18-to-34 demographic to influence advertisers and tastemakers? The new big data paradigm means my age doesn’t matter as much as it used to — I can influence the culture just as much from my new demographic as I did in my old one.

“It’ll matter just as much,” Maicon said.

Thank god for getting older.

The Millennial Problem

Major League baseball fans turning gray while Millennials tuning out

Travis Tobin turned to his 8-year-old son, Gus, as they sat in Section 106 of Target Field last week and asked: “Is this boring?”

Gus, wearing a Twins hat and T-shirt, shook his head “no.” He chewed on his glove and followed the action attentively, even as minutes passed between balls in play. His mother, Erin, noted the interest he gained after watching the movie “Sandlot.”

Gus’ sister, Anna, 4, had another opinion. She was draped across her dad’s leg, desperately needing something to distract her from the 90-degree heat.

“She’ll probably fall asleep,” Erin said.

This is the challenge baseball has in 2018: to get more kids like Anna — not to mention millennials — hooked into the game like Gus. A television screen isn’t the only screen in a household demanding attention.

There are computer screens, smartphone screens, tablet screens. Then there are so many applications within those screens — Netflix, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, Facebook — fighting for that time.

Baseball’s summer monopoly ended long ago. If it expects to thrive into the future, it must keep courting youth and convincing them the sport is great entertainment. Will improving pace of play help? Getting more balls in play and fewer strikeouts?

“There’s got to be more to it than that,” Twins President Dave St. Peter said.

Reading the numbers

St. Peter isn’t afraid to say that he, the president of a baseball team, can’t make it through a whole game without doing something else.

“And I don’t apologize for that,” St. Peter said. “I have my phone and I can see if something is going on, I can go back.”

But St. Peter is also quick to say baseball is not unique in that way.

“I hope baseball is not held to some higher standard …” he said. “Because I think people do that with other sports as well.”

The challenge is getting fans, especially young people, to tune in at all.

The Tobins drove seven hours from Winner, S.D., traveling in part because of their son’s relationship to the team.

“It’s been nice [for him] to get to know the players,” Erin Tobin said. “That helps.”

Added St. Peter: “I admire what the NBA does as it relates to the marketing of their stars. I think we have room for improvement not just as an organization but as an industry.”

For instance, baseball’s reigning MVPs, Giancarlo Stanton and Jose Altuve, have a combined 541,000 followers on Twitter, and superstar Mike Trout has 2.5 million.

James Harden, the NBA’s MVP, has 5.85 million Twitter followers, and nobody in baseball comes close to LeBron James’ 41.1 million.

Across the industry, MLB is losing interest with younger fans, even if the sport isn’t in a state of crisis.

According to Nielsen Scarborough research from 2016-17, baseball is still most popular with older demographics, with 32 percent of people ages 50-69 saying they are “very” or “somewhat” interested in baseball. That number drops to 25 percent for those 21-34 and 23 percent for ages 18-20.

Baseball still is the second-most-popular sport behind the NFL when taking those metrics into account, but it is losing ground with younger fans compared to older age groups. The NBA is gaining ground on baseball, especially in the youngest demographics.

Where baseball sees glimmers of hope is in its participation numbers. According to the Sports and Fitness Industry Association, the number of people playing baseball has increased the past three years, with more than 14.7 million people reporting that they played baseball at least one time during 2016.

This comes even as both Little League and Babe Ruth baseball reported small decreases in participation in recent years.

“One of the challenges baseball has is how unactive it is as a youth participatory activity,” said Douglas Hartmann, a sociology professor at the University of Minnesota. “Most of the parents, they don’t care that much about any particular sport. They want the kid running around, getting exercise.”

There’s also pressure for kids to specialize in one sport at a younger age. That’s one reason why participation in baseball shrinks from about 4.5 million between the ages of 6-12 to 2.5 million from 13-17.

Still, the Sports and Fitness Industry numbers matter a lot to MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred, who says they prove baseball is on firm footing.

“The single biggest determinant of whether somebody is going to be a fan as an adult is what they play as a kid,” Manfred told the Star Tribune. “We do feel like the participation numbers give us a real bedrock in terms of growing the game.”

Hooking them

The Roseville “C League” features baseball players ages 7-9, with the teams named after major league franchises.

The Astros, for example, have the bright orange jerseys and Houston’s signature star on the cap. Coach Mike Breen said most of the players, including his son, wear the uniforms proudly even if they know very little about the defending World Series champs.

“Here you have the Astros, the best team in baseball, and my kid likes baseball and plays it, but he couldn’t tell you where Carlos Correa plays or who Jose Altuve is,” Breen said.

Breen said issues such as pace of play and a record-setting number of strikeouts might have an effect on kids’ love of baseball, but it hasn’t scared away his own son from watching. Like St. Peter, he said one big issue is marketing of the players.

“If [baseball] is on TV he’ll sit down and watch it with me and be very engrossed in it,” Breen said. “Once they’re there, they’re invested in it. It’s not something they’ll kind of watch first and leave.”

Another challenge for MLB is permeating all the devices and screens younger audiences have at their disposal. A kid might not search for baseball on the TV remote. So baseball has made a concerted effort to reach different platforms, including broadcasting a game per week on Facebook.

“I’m not sure there is any media content that is strong enough to draw — pick an age group — 21-and-under audience to network television,” Manfred said. “That’s not where they consume. You have to be where they want to be.”

One encouraging sign MLB has gleaned from these broadcasts is the age of the average Facebook viewer — 36.

“Literally decades younger than what we get with a broadcast audience,” Manfred said.

That’s the same age as the audience for a recent Twins-Brewers matchup that was the Facebook game of the week. That’s significant because the number of Twins viewers ages 18-34 has declined just under 10 percent since a 2012-13 Scarborough survey, according to the team. The Scarborough numbers suggest the Twins aren’t alone in that decline.

“Whether it’s soccer or softball or even football, which takes a long time, it’s pretty predictable, whereas baseball, it’s main predictability is it’s going to be a long time,” Hartmann said. “So I think as consumers, people have a different relationship to [baseball] for sure.”

Coming together

But baseball would like consumers to have the same relationship to its game as they do to other sports. Sports are a communal experience. People watch games and comment online with friends and strangers alike.

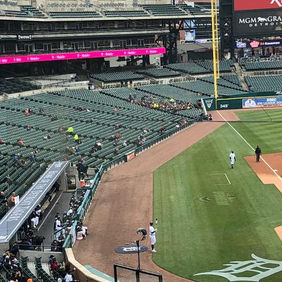

Manfred said stadiums have focused on creating more social spaces for fans to congregate and experience the game atmosphere without being glued to their seats for nine innings. This includes Target Field, which just opened its Bat and Barrel club in right field.

“It’s not about hanging on every pitch,” St. Peter said. “It’s about being a part of the crowd.”

The Twins are employing a technology known as Fancam to get data on the ages of people coming to Target Field. The technology scans the crowd and can tell by looking at a person’s face how old he or she is. It doesn’t use the technology to figure out who people are, just their ages.

In an encouraging sign for the Twins and MLB, 63 percent of attendees at Target Field are 40 or younger — and the Twins have only had a slight dip in total attendance compared to the rest of the league. As a whole, MLB is on pace to have its lowest attendance mark since 2003. Perhaps it’s no coincidence this is also the year when five teams are tracking toward losing at least 95 games. The Orioles, on pace for 117 losses, started a new promotion this year, in which each adult who buys an upper-deck ticket gets two free tickets for children 9 and under. Still, attendance in Baltimore has plunged by 7,500 fans per game.

St. Peter said when Twins fans choose not to renew seasons tickets, they don’t often cite pace of play or game length as the reasons they are relinquishing tickets.

“We see it more around data for people who are watching games, listening to games,” St. Peter said. “I think [those issues] have more impact away from the ballpark than inside the ballpark.”

St. Peter and Manfred haven’t adopted the sky-is-falling narrative that seems to permeate the discussion over baseball’s future. There are reasons for concern, not panic. Baseball can alleviate some of those concerns if it is successful in bringing more kids and young adults to the game and keeping them entertained. Not an easy task, but not impossible.

“We spend a lot of time as an industry, I think, talking about and analyzing what we think is wrong with baseball; I don’t know that we spend enough time as an industry championing what is right with baseball,” St. Peter said. “And I still think there’s a lot of things that are right.”

A Powerful Cohort

How are Millennials Changing the Sports Engagement Landscape

Chasing the millennial audience is becoming a full-time pastime for brands and marketers, who are usually left trying – and failing – to keep up with the latest technological and sociological whims. This has certainly been seen in the world of sports, where there’s been a lot of hand-wringing over how to engage with an audience that has been alarmingly resistant to the traditional channels of engagement.

Over the past few years, TV audiences for major sports have been getting smaller – and older. ESPN has lost 10% of its subscribers in three years, while the 2016 Olympics was watched by nearly 3 million fewer people on average than the 2012 tournament. It also drew its oldest audience ever, with an average age of 53, up from 45 in 2000.

This is a trend that applies to almost all major sports in the US, with only women’s tennis seeing the average viewer age drop, but even that remains high at 55. Major League Baseball’s average age was even higher at 57, with just 7% of its audience coming from the under-18s, while NFL isn’t faring much better, with an average age of 50 with fans under 18 making up just 9%.

So why aren’t millennials tuning into sports?

To engage with an audience – any audience – you need to understand them and know where to reach them. The evidence from a McKinsey report shows that millennials aren’t watching sports in the same way as older generations, with live streaming playing a much bigger role in how they consume sports content, using streaming apps almost twice as often and being much more likely to use unauthorised streaming sites.

They’re also much less likely to engage with advertising, with Nielsen’s Millennials on Millennials report showing that under-35s score an average ad memorability of 38% compared to 48% for the over-35s, largely because they are more likely to be second-screening.

McKinsey’s report showed that millennials engage more with some sports than others, with much smaller differences in engagement compared to Generation Xers when it comes to football, basketball and UFC. One area where engagement is higher for millennials than their slightly older counterparts is when it comes to women, who make up 45% of millennial sports fans compared to 41% in Gen X.

The role of social media in how millennials engage with sport is crucial, with 60% using it to check scores and sports news, while they also expect to be able to engage with their sports stars – and hold them accountable when they fall short of the expected standards on or off the field.

Engagement has to be a two-way street, and when brands or organisations forget this, they can’t expect to hold the attention of a millennial audience.

In the case of the 2016 Olympics, the IOC gave a case study in how not to engage with a millennial audience by banning the use of any unauthorised gifs or Vines of ‘Olympic Material’, thus preventing sports writers and broadcasters from using a powerful engagement tool on social media to talk about the events.

This seemed particularly ill-advised, given the amount of Olympic coverage drawn from one single fencing bout four years earlier, which drew far more attention to the sport than it would normally have received. MLB had earned criticism a year earlier for taking a similar stand against journalists using gifs from games, having previously pondered a 48 hour ban on gifs being used.

The logic behind these decisions is easy to understand, as the likes of the IOC and MLB will have been wary of losing control over their most valuable asset – the TV coverage rights – but it completely misunderstands how millennials interact with their events, and everything else in their lives.

Sharing gifs of dramatic, funny or emotional events as they happen is a part of how millennials converse with each other, so slapping a ban on them is guaranteed to turn them off what you’re trying to sell, which is getting them to care about your sport.

The sports engagement landscape is constantly evolving to meet the needs of its key audiences, and we’ve already seen brands try to play catch-up with mixed results. Millennials engage with sport differently from the generations above them, but that is an opportunity rather than an obstacle for brands that are willing to deliver them content in the way that best fits their lifestyles.

Are Millennials Really a Problem?

We are wrong about Millennials; they ARE sports fans

Many sports executives fear that the root cause of declining TV viewership and aging audiences is the disengagement of millennials from live sports. But the belief that millennials are to blame is misplaced.

We aren’t losing fans, we are fighting short attention spans

From Nielsen data, in the 2016-17 regular season, NFL ratings among millennials declined 9 percent. However, the number of millennials watching the NFL actually increased from the prior season by 2 percent. The ratings decline was caused by an 8 percent drop in the number of games watched and a 6 percent decline in the minutes watched per game. The same was true for MLB, NBA and NHL. With so many sports options across so many screens, fans of all ages are clicking away from low-stakes or lopsided games.

Millennials versus Gen X: The wrong way to segment sports fans

As sports executives seek to build new direct-to-consumer channels, McKinsey’s proprietary research suggests that age is an ineffective way to target digital sports fans.

Millennials are sports fans too. Although more Gen Xers than millennials follow sports closely (45 percent versus 38 percent), the gap disappears for NBA, UFC, MLS, EPL and college sports.

Most millennials have cable. As of November 2016, 78 percent of millennials had cable, satellite or telco TV service at home. That’s pretty close to the 84 percent of Gen Xers with pay TV.

It’s not about getting older, it’s about having kids. It’s true that on average, millennials watched 28 percent fewer hours per week of TV in 2016 than people their age did in 2010, whereas Gen X viewing slipped by only 8 percent over the same period.

However, when Nielsen segments millennials into those living with parents, those living on their own, and those starting their own families (at age 27, all three segments are about equal in size), big differences emerge. Millennials with kids watch 3 hours and 16 minutes of live TV a day, fully 55 percent more than millennials living on their own and just 14 percent less than Gen Xers under 49. Millennials living on their own spend 15 percent more time out of their homes and are 31 percent more likely to own a multimedia device than millennials with kids.

Millennials still watch live games. Millennial sports fans watch just 6 percent fewer live games per week than Gen X.

Everyone’s digital. Virtually everyone in Gen X owns a smartphone, as do millennials. The two groups own multimedia devices (36 percent versus 40 percent) and use online subscription video on demand (68 percent versus 75 percent) at nearly the same rates. And they both spend over five hours a day on smartphones and PCs.

A difference of degree: Streaming and social media

For all the similarities in technology adoption and viewing behaviors, millennials differ from their parents’ generation in two ways that matter to sports rights holders.

Millennials stream sports more often. Millennials stream almost twice as much as Gen X (56 percent versus 29 percent). They are also more likely to admit to using unauthorized sports streaming sites (20 percent versus 3 percent).

Millennials are social fans. While millennials and Gen X use sports sites and apps equally, significantly more millennials follow sports on social media. For example, 60 percent of millennial sports fans check scores and sports news on social media versus only 40 percent for Gen X. Twice as many millennials use Twitter, and five times as many use Snapchat or Instagram for that purpose. YouTube dominates sports highlights for millennials.

However, the gap is closing: Gen X is growing social media usage 38 percent faster than millennials.

Implications: Targeting digital sports fans

Given the similar trends in sports viewing among millennials and Gen X, how should sports marketers target digital fans?

■ Target mobile viewers of live streams. In predicting the number of live sports events watched per week, we found that generation (i.e., millennial versus Gen X) was not statistically significant. Those who watch live sports on mobile, however, watch 20 percent more live sports events than those who do not.

■ Convert the pirates. Fans who admit to watching unauthorized streams watch 22 percent more games (across all platforms) than those who do not.

■ Target moms. Male sports fans with children watch 14 percent fewer live games than those without, but women with children watch 24 percent more sports events than those with no kids.

■ Promote tickets on social media. Teams know to target fans making more than $100,000 a year (51 percent of whom attend live games versus 40 percent of those earning less than $100,000), but they may not know that 56 percent of fans who follow athletes or teams on social media attend games (versus only 30 percent of fans who do not).

■ Highlights are the gateway to subscription video. Fans who consume more than 30 minutes a day of sports highlights are three times as likely to subscribe to sports OTT services as fans who do not.

Implications: Innovating the digital sports experience

The problem of declining attention spans will not be solved merely by replatforming TV video for PCs and mobile devices. As sports marketers develop new digital products — including services for livestreamed events, highlights, fan commentary, news, analysis, etc. — they should design for new, digital behaviors that cut across generations:

■ Shorter viewing sessions (e.g., with whip-around viewing and quick navigation to other games).

■ One-click tune-ins from social media or search, prompted by alerts on high-stakes game situations.

■ Convenient access, e.g., the ability to watch any game for my favorite team or player or fantasy player, regardless of the TV network on which they are broadcast.

■ Rapid, simple sign-on and payment (ideally using fingerprints or other biometrics).

■ Quick navigation between fantasy sports rosters and live streams, especially for avid DFS players (and sports bettors).

Gen X wanted its MTV. Millennials have Fear Of Missing Out. Both generations are consuming digital sports voraciously, at the expense of traditional TV viewing. Sports marketers who target the right digital behaviors, rather than traditional viewer segments, and develop digital products to take advantage of them will build stronger fan bases than ever before.

Plenty of Good Sections Still Available

Attendance Problems are Real

Keeping fans in the stands is getting harder to do

Major League Baseball's All-Star game Tuesday night is set to draw a full house. Some 45,000 people are expected to fill all the seats of Citi Field, home of the New York Mets.

But the game appears to be an exception rather than the rule this year when it comes to putting fans in baseball stands. MLB's total game attendance is down by 417,192 people so far compared with last year at this time, according to Baseball Reference.com.

In fact, live attendance in other U.S. sports—pro basketball and football, motor sports and even college football—has declined or leveled off the last three to five years.

"The drop-off in attendance for live sporting events is getting worse," said Lee Igel, a professor of sports management at New York University.

"You've got a lot of competing factors in this, even bad weather," Igel explained. "But with the economy still sorting itself out, there's the huge cost of going to live events plus fighting through traffic and parking just to get to the games."

"And even more important is the experience of watching games in the comfort of your home on a big screen without the hassle at a stadium," Igel said. "That keeps a lot of people away."

Different sports, same problem—except hockey

The fall off in baseball attendence has gotten so bad, that the Miami Marlins—the MLB team with the lowest attendance figure this year as well as the worst win-loss record—decided to close the upper bowl of their stadium for some upcoming home games.

Even baseball royalty, the New York Yankees, have seen a decline this year of nearly 2,500 fans per game and are selling half-off tickets through the online coupon service Groupon. Their bitter rivals, the Boston Red Sox saw their record 820-game sellout streak come to an end this summer.

This past season, several lower level National Basketball Association teams, like the Sacramento Kings, the Detroit Pistons and the Milwaukee Bucks, had major attendance drops. The Pistons averaged only 13,272 tickets sold per home game while playing in the 21,000-seat Palace arena.

To lure fans for a game against the NBA's Dallas Mavericks in early December, the Phoenix Suns offered a money-back guarantee on tickets, promising that fans could get a refund if they weren't satisfied with the team's performance, or even if the beer in the arena was flat.

The attendance drops have spread like a fan wave. A NASCAR auto race in March—the FC 500 in Bristol, Tennessee—had a reported attendance figure of 80,000 people, but that left a half-empty speedway that normally fills up with 160,000 for the race.

For 30 of 35 college football bowl games this past season, the average announced attendance was 46,278—down 5 percent from 2011-12 and 8 percent from 2010-11 through those same games.

Attendance at NFL games this past year was up slightly according to the NFL, but that was after some 4 years of decline. The league reached an all-time high in 2007—18,137.224 total attendance— but in 2011, dropped to its lowest level,17,391,163, since the league expanded to 32 teams in 2002.

Only pro hockey, with its rabid fan base returning after a lockout and shortened season this past year, saw an attendance increase for a third consecutive season.

"All the major sports except hockey have major challenges getting people to attend live events these days," said Mark Conrad, a professor of sports law at Fordham Univeristy.

"Most sports can't just depend on die-hard fans to fill up seats," Conrad said. "They've had to offer a lot more than just the game."

Like a trip to Disneyland?

To entice fans—while forgoing money-back guarantees—stadiums have built mini theme parks for families while expanding traditional ballpark food like hot dogs, hamburgers and garlic fries to sushi, fresh sliced tuna and gluten-free and vegetarian offerings like gourmet salads.

"There are more firework nights, rock concerts and even religious nights in some parts of the country to bring people in," said Mark Conrad.

"It's more like a trip to Disneyland than a ball game," said Lee Igle. "The questions is, is this enough to bring fans in? Some that might just want to sit back and enjoy a game might think it's overload."

Expanding on the comforts of home theme, the NFL's Jacksonville Jaguars are considering airing the league's RedZone Channel on its massive video boards, This would give fans at EveBank Field a chance to view any NFL game as soon as one team gets down within their opponent's 20 yard line.

"We know we are competing with ourselves when it comes to watching games at home or coming to the stadium," said NFL spokesman Brian McCarthy. "The RedZone Channel expands the stadium offerings."

"With 4-6 hours of pregame shows, the home big screens and the ability to change channels, the home experience is phenomenal," McCarthy said. "That's why we're doing everything we can to enhance the stadium experience, like possible cameras in the locker rooms that would show up on the stadium big screens and offering fantasy sports packages."

Fan enchancement also includes easier driving to the stadiums, said McCarthy.

"We're looking into how we can work with local officials to improve traffic patterns for fans and making parking easier," he explained. "We also want to have the best technology, like Wifi, so fans don't miss out on their tech needs."

Ticket prices keep rising

As for sports ticket prices, they've gone up over the years—and not without a touch of irony. As teams try to attract more fans with expensive top-tier players and new or refurbished stadiums, that's making it more costly to attend games.

According to research firm Statista, the average NFL ticket in 2012 was $78.38, a 2.5 percent increase from 2011. Tickets averaged only $67.11 in 2007.

The NFL's New England Patriots have the current highest average ticket price at $241.86.

The average price today for a Boston Red Sox ticket is $88, the highest among baseba;; teams, according to MLB. Topping the NBA average ticket price is the Los Angeles Lakers, at $169.80.

"All sports are aware of prices and very conscious of the issue," said the NFL's McCarthy. "We're (the NFL) looking at more flexibility for fans when it comes to paying for them."

Many teams like the NBA's Orlando Magic and MLB's San Diego Padres are using dynamic pricing. This allows teams to lower or raise prices on game day tickets and fill up empty seats that haven't sold.

"It's a new way to bring in fans and sell tickets to games that wouldn't ordinarily sell," said Mark Conrad. "You can fill in seats at a reduced price and maybe get those fans to come back and pay more at another game."

An 'ongoing issue'

But offering dynamic pricing or a wide ranging sushi menus or a theme park with water slides or thousand of Wi-Fi outlets—or anything else sport execs can think of—is unlikely to give fans enough reason to show up in person, say analysts.

"The love of sports isn't going away in this country but I do think the decline in attendance will keep happening," said NYU's Igel. "Most people just don't have that type of discretionary income anymore to spend on sports."

"I do see this is as an ongoing issue," said Conrad. "The only real way to get fans in the seats is to have a winning team. And even that's no guarantee these days."

The NFL's McCarthy said he's hoping enough fans still see the difference between being at a live event and staying home.

"We know it's more comfortable sitting on a couch," he said. "But the players can't hear you from there."

...and they're not getting any better

MLB's attendance problem is getting worse

NEW YORK — The Tampa Bay Rays and Miami Marlins drew 12,653 Wednesday night — combined.

Baltimore, Cincinnati, Minnesota and Tampa Bay set stadium lows this year. Kansas City had its smallest home crowd since 2011 and Toronto and San Francisco since 2010. The Marlins’ average attendance is less than Triple-A Las Vegas.

Major League Baseball’s overall average of 26,854 through Wednesday is 1.4 percent below the 27,242 through the similar point last season, which wound up below 30,000 for the first time since 2003.

Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred attributes this year’s drop to fewer season tickets but emphasizes day-of-game sales are up 6 percent.

“Given the explosion of entertainment alternatives and the growth of the secondary market, it is not surprising that season ticket sales can be challenging,” he said. “The clubs are responding to this challenge with creative and effective approaches. For example, sales of subscription tickets are double what they were a year ago. And the Twins recently had a $5 flash sale that produced crowds of over 30,000 in three of four games, and the largest single-game attendance since 2016.”

Nineteen of the 30 teams have seen their average fall from a similar point last year, with the largest drops in Toronto (6,963), San Francisco (6,463), Baltimore (3,839) and Detroit (3,686).

Large rises have taken place for Philadelphia (10,383), Oakland (4,027), San Diego (3,465) and the Chicago White Sox (2,311). The Phillies signed Bryce Harper and the Padres added Manny Machado.

“A lot of it comes down to competition. Fans want to know their teams are doing everything they can to compete for a championship every year,” union head Tony Clark said. “I see every empty seat as a missed opportunity. Experiencing a game and seeing players perform in person creates a bond with baseball; our industry needs to find ways to convert those empty seats into lifelong fans.”

MLB’s average peaked at 32,785 in 2007 — the last year before the Great Recession and the next-to-last season before the New York Yankees and Mets moved to smaller stadiums. The average was at 30,517 in 2015 before sliding for three straight years, and last season’s final figure of 28,830 marked a 4% drop, the overall number hurt by unusually cold and wet weather early in the season.

Manfred points to other metrics that please MLB: Games top prime-time cable ratings in 24 of 25 markets and MLB.tv streaming is up 8.5%. He sees increases for the Phillies, Padres, Athletics and White Sox tied to team performance.

Florida remains a problem on both coasts.

Despite a sparkling, eight-season-old ballpark with a retractable roof, Miami is averaging 9,554 in Derek Jeter’s second season as chief executive — below the 9,582 average for Triple-A Las Vegas in its first season at a new 10,000-capacity stadium.

Tampa Bay plays in one of the most outmoded facilities in the major leagues and drew 5,786 against the Blue Jays on Tuesday, the smallest home crowd for the Rays, who started play at Tropicana Field in 1998.

“The more people there are, the more energy there’s going to be,” Tampa Bay outfielder Kevin Kiermaier said. “No matter what crowd you’re playing in front of, you have to get motivated.”

A quartet of last-place teams has seen swaths of empty seats.

Miami is on track to have the lowest home attendance in the National League for the seventh straight season. Tampa Bay is at the bottom of the AL for the fifth consecutive year.

“Any time you’re seeing less people show up to the ballpark, I think you’re wondering why and you’re wondering how you can change that,” said Miami first baseman Neil Walker, accustomed to big crowds from his time in New York. “You’ve got to assume that it has a little bit to do with it being expensive to come to the ballpark.”

Having traded many veterans, the Orioles are 28th in the majors at 16,263. Baltimore topped 2 million in 21 of its first 25 seasons at Camden Yards, exceeding 3 million nine times. But the Orioles drew 6,585 against Oakland on April 8, the lowest in the ballpark’s 28-season history except for a 2015 game closed to the public at a time when the city was plagued by rioting.

“I wish fans were here. When we played in Wrigley, the energy level was off the charts,” first-year Orioles manager Brandon Hyde said. “I’m hoping that someday soon that will be the case here.”

Cincinnati’s crowd of 7,799 against Milwaukee on April 1 was the lowest for a Reds home game since 1984 at Riverfront Stadium. That same day, Toronto drew 10,460 against the Orioles, the smallest attendance at the Rogers Centre since 2010.

San Francisco drew 28,030 vs. Pittsburgh on April 10, the Giants’ lowest home crowd since 2010.

Kansas City’s crowd of 10,024 against the Twins on April 2 was the lowest at Kauffman Stadium since 2011. Minnesota drew 11,465 against Toronto on April 17, the lowest figure in Target Field’s 10-season history.

“As a kid, I loved more than anything to go to the ballpark and I loved nothing more than playing baseball,” Walker said. “But I think a lot of people are just — they want action now. They don’t want to be totally consumed with a game maybe that’s just not timed.”

In College Football, Too

College football heads in wrong direction with largest attendance drop in 34 years

Major-college football experienced its largest per-game attendance drop in 34 years and second-largest ever, according to recently released NCAA figures.

Attendance among the 129 Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) teams in 2017 was down an average of 1,409 fans per game from 2016. That marked the largest drop since 1983 when average attendance declined 1,527 fans per game from 1982.

The 2017 FBS average of 42,203 fans per game is the lowest since 1997.

That average attendance drop marked the second-sharpest decline since the NCAA began keeping track of college football attendance in 1948. For the first time in history, average attendance declined nationally for four consecutive seasons.

The 2017 numbers include FBS home games, neutral-site games, bowl games and the College Football Playoff.

Since establishing an all-time high average attendance in 2008 (46,971), FBS attendance has slipped a record 10.1 percent over the last nine years.

Even the most rabid league in the country saw a dip. In 2017, the SEC experienced its sharpest per-game decline -- down an average 2,433 fans -- since 1992. That figure led the Power Five in fans lost per game in 2017.

While the SEC led all FBS conferences in average attendance for the 20th consecutive year, its average attendance (75,074) was the lowest since 2005. The SEC has slipped an average of 2,926 fans per game (3.7 percent) since a record 78,630 average in 2015.

College sports has long been at odds with how to manage the time/value relationship. In other words, how to make attendance at a live event more valuable than the alternatives, which range from remaining at a tailgate outside the venue to viewing on a smartphone while on the go to watching in the comfort of one's living room.

"It's a technology issue," said Wright Waters, Football Bowl Association executive director and former Sun Belt commissioner. "The public is ahead of us every day in what they can get from technology. We have not been able to keep up."

One former Power Five athletic director called it a "societal shift" leading the powers that be scrambling to figure out the viewing habits of millennials as well as well-heeled alumni.

"This is not surprising to me," said Bill Lutzen, a veteran sports TV programmer who is currently the CFO of a web optimization firm. "This issue is with lack of involvement of the college students. They no longer view attending sporting events as part of the university experience."

Student attendance had decreased 7 percent since 2009, Wall Street Journal found in 2014.

Despite leading the nation in average attendance each year since 1997, Michigan has had issues recently selling student tickets.

One Power Five source suggested the NFL and MLB have been much more proactive in downsizing stadiums to create a more premium ticket.

Arizona State, Kentucky, North Carolina and Penn State are all in the process of downsizing stadiums. In marketing circles, that creates a more intimate experience. Marketers continue to struggle to find a successful balance in stadiums. Across all leagues, that means making the game experience as close to that living room experience as possible.

AT&T Stadium in Arlington, Texas, and Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta have created in-house lounges so extravagant it's actually better watching on a cinema-quality screen with drink in hand than stepping out to view the real thing a few feet away.

"Does the experience and cost outweigh the convenience of watching it at home?" asked Brian Cockerham, vice president of PrimeSport, which sells travel and ticket packages to pro and college events. "That is why you are seeing several schools decrease capacity and [others] look to decrease capacity and look to increase the experience and amenities."

Some of the slippage nationally can be attributed to the growth of the FBS. In recent years, FCS schools with smaller fan bases and stadiums have moved up to FBS. Since 1988, Division I-A/FBS has grown by almost a quarter from 104 schools to 129 in 2018. Example: Georgia Southern last year drew a hurricane-impacted crowd of 3,387 vs. New Hampshire.

But across all divisions, 1,693,661 fewer fans attended games in 2017 compared to 2016. That's the biggest per-year drop since 2004. Although the average decline for FBS, FCS, Divisions II and III was only 380 fewer fans per game, that marks the sharpest year-over-year drop since 1993.

Bowl game attendance also declined for the seventh straight year to an average of 40,506 in the 40 games. That marks a 23 percent drop-off in average bowl attendance since 2010.

"Are we concerned about it?" Waters asked. "You're damn right."

Waters said a mitigating factor in bowl attendance dip is an expansion in recent years to several smaller venues.

The total of 47.6 million fans who attended NCAA football in 2017 is down almost 2.7 million fans (5.3 percent) since an all-time high of 50.3 million in 2013.

In fact, there were indicators across the board that fewer fans are paying the price of admission to actually watch games.

-

Despite an uptick in the number of teams playing NCAA football (666), the total amount of fans (47.6 million) were the fewest since 2005.

-

In the latest realignment era (since 2012), Power Five conference attendance is down an average aggregate of 11,383 fans per game. Only the SEC is up in average attendance (+128) during that six-year period.

-

The Pac-12 has experienced the biggest overall drop of any Power Five league: 4,078 fans per game since 2012. Its 2017 average of 49,601 is the conference's lowest average attendance since 2001.

-

The ACC experienced its lowest average attendance (48,442) since 1999 (45,073). The 2017 figure was the lowest among Power Five conferences for the 13th straight year.

-

Only the Big Ten and Mountain West had average per-game increases in attendance from 2016. In once again leading FBS in attendance, Michigan (111,589 per game) posted the six largest crowds of 2017.

-

Purdue had the largest attendance increase (up 13,433 per game) going from 34,451 in 2016 to 47,884 in 2017. The Boilermakers won seven games for the first time since 2011.

Losing Viewership

TV Ratings: Why is the NBA Shooting Air Balls?

The NBA’s TV ratings so far this season have been far from all-star level.

Viewership across ESPN, TNT and NBA TV is down 15% year-to-year overall, according to Nielsen figures. TNT’s coverage is averaging 1.3 million viewers through 14 telecasts, down 21% versus last year’s comparable coverage, while on ESPN the picture isn’t much prettier. The Disney-owned network is down 19%, averaging 1.5 million viewers versus just under 1.9 million viewers at the same stage last year.

But why have the numbers been stuffed? And do the NBA, TNT and ESPN have cause to be deflated by the drop? According to sources at all three organizations, injuries have played the biggest part.

So far this season, 63% of games on ESPN and TNT (or 22 games out of 35) were missing one or more stars missing due to injury. Eleven of the 14 games broadcast on TNT have had one or more stars missing due to injury, and 11 of the 21 ESPN games have had the same problem, per the league.

It has to be said that the list of big-name stars sat in civilian clothing instead of in uniform has been freakishly long. The most controversial absence has been that of Kawhi Leonard, the freshly-minted Los Angeles Clipper who almost singlehandedly led the Toronto Raptors to an unlikely championship victory last year. Leonard’s absence has drawn headlines because many attribute some of the games he has missed to “load management,” or rest. However, one source pointed out that the only national TV games he has missed so far have been due to “injury management” as opposed to scheduled rest.

Also on the list of absentees are Golden State Warriors stars Stephen Curry and Klay Thompson, recent Brooklyn Nets acquisitions Kevin Durant and Kyrie Irving, and Leonard’s fellow Clippers star Paul George.

Add to that the fact that number one overall draft pick Zion Williamson hasn’t played a single minute of NBA basketball yet. Excitement around the New Orleans Pelicans rookie entering the league was at fever pitch before the season, and the NBA was clearly hoping that his presence would provide a boost in ratings. Of the games on ESPN and TNT so far, six have featured the Pelicans, the second highest number for any team behind only the Clippers, tied with the Boston Celtics, and ahead of bigger teams like the Golden State Warriors.

Speaking of the team from the bay area, another contributing factor to the league’s ratings struggles has been the Warriors’ terrible performance. The Warriors currently find themselves at the very bottom of the Western Conference standings with a 4-19 record, the worst in the NBA, behind even the train wreck that is the New York Knicks. After dominating the league for the last five years and drawing heft ratings in the process, it would appear that the Warriors’ dynasty is crumbling and their ratings draw along with it.

Another potential factor behind the ratings decline is that TNT has face increased competition from a resurgent “Thursday Night Football” on Fox, and both TNT and ESPN faced more head-to-head competition with baseball’s World Series in October than in previous years.

The opening night game between the Lakers and Clippers on TNT competed directly with game 1 of the World Series, while ESPN competed with games 2, 3 and 7 later in October, after only competing with game 2 of the 2018 Major League Baseball event.

Come the business end of the season the numbers are going to improve — they always do with the NBA. Eighty-two regular season games is a lot for anyone but the most ardent fan to get through. And of course viewership on cable is down pretty much across the board. The damage caused by cord-cutting is hitting cable hard and it likely won’t stop anytime soon.

While sources say no one at the NBA, ESPN or TNT is pressing the panic button quite yet, the league has been eyeing changes for several years that it believes could boost those numbers. The biggest of which is a midseason tournament, an idea which NBA commissioner Adam Silver has reportedly been floating for several years. Such a tournament would take place between Thanksgiving and Christmas, avoiding the NCAA March Madness tournament and the NFL playoffs, and involve all 30 teams, with the hope of providing a jolt in NBA interest at a time when sports fans are usually locked in on the pig skin.

Whether or not such proposed changes, if they even happen, will give the league a much-needed ratings boost is uncertain, but what is for sure is that TNT in particular is hoping its rear-loaded broadcast schedule will restore the ratings balance later in the season.

The WarnerMedia network has only had one Lakers game so far, with 11 more to come throughout the season, as well as eight more Clippers appearances on the way.

All involved will be hoping those games rain threes in ratings terms, rather than shooting airballs.

The Daryl Morey controversy explained

With just one tweet, Daryl Morey set off a geopolitical firestorm.

The Rockets general manager found himself at the center of controversy after he sent out a seemingly straightforward message on social media. But Morey's six-word post pushed the NBA into a difficult dilemma with China, and there doesn't appear to be a simple resolution in sight.

Here's how the situation started, the intense reactions that followed and what could come next.

What did Daryl Morey tweet?

In a since-deleted tweet on Oct. 4, Morey shared an image with this slogan: "Fight for Freedom, Stand with Hong Kong."

Why did the tweet spark so much controversy?

Morey inadvertently inserted the NBA into the middle of a heated debate over civil rights and extradition laws.

A piece of legislation introduced over the summer in Hong Kong proposed the ability to extradite criminal suspects back to China, dropping them into a Chinese justice system in which most criminal trials end in a conviction. There were immediate concerns about protecting the civil rights of citizens and preventing them from being targeted unfairly.

The nature of the bill inspired numerous anti-government, pro-democracy protests, and some of the demonstrations turned violent. Chief Executive of Hong Kong Carrie Lam later declared the bill "dead" but only withdrew it after months of protestors demanding she formally do so.

How did the Rockets and China react?

Rockets owner Tilman Fertitta quickly distanced the organization from Morey's comments, and Morey later walked back his statement. All-Star guard James Harden also publicly apologized to China in the aftermath of Morey's tweet.

The Ringer's John Gonzalez reported that Morey's job may be in jeopardy, but The Athletic's Sam Amick shot down the idea that Morey could be fired, citing two sources close to Rockets ownership. When asked about the reports, Fertitta called Morey the "best general manager in the league" and said "everything is fine with me and Daryl."

In the eyes of China's leadership, Morey represented a foreign power encouraging these demonstrations. The Chinese consulate in Houston denounced Morey's tweet, saying it was "deeply shocked" by his "erroneous comments." The Chinese Basketball Association ceased all cooperation with the Rockets, and CCTV, the state-run television station, has suspended broadcasts of games.

China's Education Bureau also canceled a scheduled NBA Cares event in Shanghai. The NBA and the Nets were set to dedicate a Learn and Play Center at a local school. A separate NBA Cares event involving the Lakers was also canceled only hours before its scheduled start time.

Nets owner Joseph Tsai, co-founder of the Chinese company Alibaba, offered his own personal response to the "third-rail issue" with a lengthy Facebook post, claiming that "1.4 billion Chinese citizens stand united when it comes to the territorial integrity of China and the country’s sovereignty over her homeland." Tsai said he would accept Morey's "apology" but added "the hurt that this incident has caused will take a long time to repair."

And what about the NBA?

The NBA issued an initial statement that was roundly criticized by U.S. politicians on both sides of the aisle for choosing financial interests over human rights.

Here is that statement in full:

We recognize that the views expressed by Houston Rockets general manager Daryl Morey have deeply offended many of our friends and fans in China, which is regrettable. While Daryl has made it clear that his tweet does not represent the Rockets or the NBA, the values of the league support individuals' educating themselves and sharing their views on matters important to them.

We have great respect for the history and culture of China and hope that sports and the NBA can be used as a unifying force to bridge cultural divides and bring people together.

NBA commissioner Adam Silver then attempted to clarify the league's stance with a follow-up statement in which he claimed the NBA is about "far more than growing our business."

"It is inevitable that people around the world — including from America and China — will have different viewpoints over different issues," Silver said. "It is not the role of the NBA to adjudicate those differences.

"However, the NBA will not put itself in a position of regulating what players, employees and team owners say or will not say on these issues. We simply could not operate that way."

Why does the NBA's relationship with China matter?

China has been a major market for the NBA ever since the Rockets selected Chinese center Yao Ming with the No. 1 overall pick in the 2002 draft. Yao is one of the most important figures in the history of the sport in terms of the globalization of the NBA. His mere presence allowed the Rockets to become China's team. By 2006, Houston forward Tracy McGrady had the top-selling jersey in China, even above Yao.

Nearly a decade removed from Yao's retirement, the Rockets are considered the second-most popular team in China, according to a recent study, behind only the Warriors. Golden State features two-time MVP Stephen Curry and five-time All-Star Klay Thompson, who has an exclusive shoe deal with Chinese company Anta.

The doors Yao opened into the Chinese market have allowed the league to build a multibillion-dollar relationship. The NBA has a deal in place with Tencent, a streaming platform which has temporarily suspended broadcasts, reportedly worth $1.5 billion, and NBA China is worth more than $4 billion, according to Forbes.

Two Chinese companies — sportswear brand Li-Ning and Shanghai Pudong Development Bank — have suspended their sponsorship agreements with the Rockets, according to Reuters.

What happens next between the NBA and China?

Silver, speaking to "Good Morning America" co-host Robin Roberts at the TIME 100 Health Summit, claimed that Chinese leadership requested Morey be fired. (Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang said no such demand was made by the Chinese government, according to the Associated Press.)

"We made clear that we were being asked to fire [Morey], by the Chinese government, by the parties we dealt with, government and business," Silver said. "We said there's no chance that's happening. There's no chance we'll even discipline him."

Silver was surprised by the blowback because he felt the NBA had taken a "principled position" and hadn't "acquiesced" to China. He pointed to not only future monetary losses but also the instant impact of CCTV and Tencent suspending game broadcasts.

"The losses have already been substantial," Silver said. "Our games are not back on the air in China as we speak, and we’ll see what happens next. ... The financial consequences have been and may continue to be fairly dramatic."